September 9, 2013

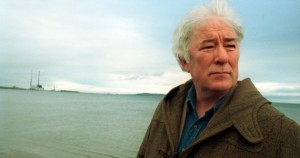

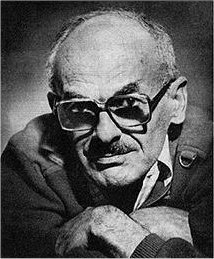

Šalvovič Bulat Okudzhava (Moscow, May 9, 1924 – Paris, 12 June 1997) was a Russian poet and songwriter originally from Georgia, a member of the Russian genre called “songwriters”. He composed more than two hundred songs and has been for her award-winning poetry, that it was set to the kind of song book, then it was picked up by other singers such as French Georges Brassens. He was known as a poet and bard (singer) after the fifties and he was considered a danger to his poems and songs: he was famous overseas, and the inability to publish at home. It is said that Brezhnev, had expressed the desire of his death, however, aware of increasing even more the popularity of this poet. Russians, in fact, sang his songs in the streets, in the taverns and bars, especially in the cold of the Russian winter evenings. He was a poet armed with a guitar and equipped with irony. His father, an activist of the Communist Party, the revolutionary of the first hour, will fall victim to one of the many purges: he was executed in the ’30s. His mother, activist too, will drink the frozen water of the Gulag for 19 years. Other nine of his relatives were executed and then everyone found innocent. Bulat, just seventeen, he walks to volunteer to defend the homeland from the Nazi threat and will hurt several times.

And he will open the eyes of the war an ally of pride and greed and he will sing of suffering expressing compassion.

Cowardly WAR – my translation.

Ah, war coward that you did!

Our courts have become silent.

Our kids raised their heads,

and they became great before time.

They were soon as seen on the street

and they departed: soldiers, soldiers …

Bye, guys! guys,

looking for you to come back! (…)

Ah cowardly war you did!

In place of marriage – chipping and smoke.

Our girls have donated

the white suits to the sisters. (…)

The rhythm of the poems have a common root with the songs of the bard: this part of the stomach, drawing on the tradition of songs, slow first and successive peaks later. A style that is characteristic of the Volga Boatmen and chants and stories the exploits of the heroes, and lovers of the disease, and then old age and death. Bulat not offer theorems and explanations: he expresses the horror in the everyday acts of war.

<< Do not believe the war, boy,

do not believe it, the war is sad,

it is very sad boy,

the war is narrow like shoes

Your good horses

we can not do anything,

you’re all in the palm of your hand

all the guns you point to. >>

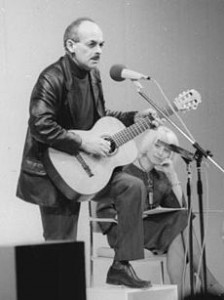

And Bulat expresses it with a sweet irony that makes us smile moved. The poet confesses during a concert: “When I started, I knew three chords on the guitar, but now, after thirty years of work are improved … I know five!”

How to sing the horror and terrible with gentleness and compassion:

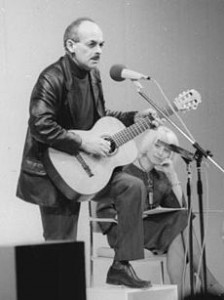

Concert in Paris, 1995. Prizes HERE

SONG OF THE INFANTRY – My translation.

Sorry for the infantry,

though sometimes it is so stupid:

always we start

when the earth explodes the spring.

And unsteadily

on the scale that boggles there is no salvation.

Only white willows

as white sisters who watch you go

Do not believe the time,

when pouring rains persisted.

Do not believe the infantry,

bold when he sings songs.

Do not believe, do not believe,

when the nightingales in the gardens cry.

The life and death

have not yet settled accounts.

Time has taught us:

live like the bivouac, open the door.

Companion man,

it is also seductive your fate:

you are always on the march,

and one thing only removing you from sleep.

Why we start

when the earth explodes the spring?

Bulat was uncomfortable and feared, because he heard from those who did not read and he was sung by those who had the look down, facing the ground, which is that it is the true engine of all rebellion and revolt of the Russian people.

WAR AGAINST A FOREIGN COUNTRY – My translation.

In a war against a foreign country the king departed.

A large bag of biscuits made him the queen,

the old coat with great care she mended,

three packs of cigarettes and also she gave the salt.

And his hands on the chest of the king went to lay

and said, caressing him with beaming eyes:

“Punish them well, otherwise you will be seen as a pacifist

and to take the spoil of good panforti you will not forget “

And the king saw that the army was in the midst of the court:

five soldiers sad five cheerful, and a corporal.

The King said: “We are not afraid printing, nor the storm.

we will return victorious after defeating the enemy base! “

But soon the triumphant exultation of the speeches ended.

In war, the king changed the attitude of the troops:

gay soldiers without delay stewards appointed

and the unhappy soldiers he left them, “Thus it will not hurt!”

Just think ‘: supervened then the days victorious.

Sad none of the soldiers returned from the war.

Corporal of dubious moral married a prisoner,

but they captured a large bag of tasty panforti

Play, orchestras; echoed, songs and laughter!

A fleeting sadness we must not give up.

It made no sense for the sad soldiers remain alive

and then they were not enough for all the gingerbread.

And he could not be imprisoned or killed because of a people expressing compassion for his children, the condition of the martyr would amplify his message that it is still alive and fresh.